The Missing Peace--An Advent Reflection on Peace

Confronting What’s Missing in Our Gospel This Advent

How do we respond to tears?

Advent is a season of hope, but it’s also a time for honesty—a time to sit with the world’s pain and let it break our hearts. As we light the second candle of peace (a tradition in many Christian circles during the Christmas season, though perhaps unfamiliar if you’re not part of a church community), I’ve been reflecting on how often we practice an airbrushed approach to the story of Bethlehem—reduced to shallow phrases on Christmas cards. What does it mean to truly follow the Prince of Peace in the face of injustice?

Rachel Still Weeps Today

At the NEME conference in Santa Barbara, my friend Bruce Fisk preached a powerful sermon titled “Rachel Still Weeps” (Matthew 2:18). He reminded us that Rachel’s tears are not confined to history; they echo today in the cries of mothers in Gaza, in Palestine, and in every land marked by suffering and oppression. His words invited us to grieve, and I found myself asking hard questions: What now? What next?

Bruce’s sermon resonated with a critique shared by Daniel Bannoura, one of our Palestinian presenters. Reflecting on how gatherings like this often play out, Daniel said, “They talk about us, but without us.” His words exposed a deeper truth: too often, we analyze, strategize, and empathize, yet fail to confront how we ourselves are complicit in the structures that perpetuate injustice. And Palestinians hear us talking about them—their lives, their struggles, and the land they live in—yet they are often excluded from the conversation and remain outside our purview.

The Software of Occupation

This critique aligns with the insights of Mitri Raheb, a Palestinian theologian who has described Christian Zionism as the “software” of occupation. Raheb argues that certain Christian beliefs—such as the idea of Israel as God’s chosen people or the land as divinely promised—function as the ideological underpinning of the occupation. This “software” justifies the “hardware” of physical domination: the walls, checkpoints, and military presence that define Palestinian life under occupation.

Raheb’s work has helped me see that The Missing Peace isn’t just about what’s absent in our theology—it’s also about what’s actively present. These theological constructs, often embraced uncritically, perpetuate injustice by embedding colonial narratives into the religious consciousness of many Christians, particularly in the West.

The Missing Peace in Our Theology

The Missing Peace identifies the injustice we support and perpetuate—often unknowingly—against Palestinians, Native Americans, and others who have been marginalized and oppressed. As Christians, we’ve reduced the Gospel to what’s “just about us”—our personal peace with God. In doing so, we’ve sidelined the broader call to justice, fairness, and peace for others. The good news becomes a privatized, partial gospel, one that prioritizes inner comfort but neglects outward compassion.

Glenn Stassen captures this problem so well when he writes:

"The word peace appears 100 times in the New Testament, but theologians…often limit it to individual reconciliation with God—without significant attention to God’s work to reconcile us with others or with enemies—and sometimes move it off the stage of history into a purely future eschatology waiting in the wings invisible in our actions and invisible to observers’ eyes."

This critique exposes the Achilles’ heel of much evangelical theology: a dispensational framework that places justice and reconciliation off in a distant, abstract future while neglecting the tangible, visible call to action in the here and now.

We see this disconnect in the way scripture is applied. Christians often embrace the Ten Commandments—laws of prohibition—but shy away from the radical, restorative ethics of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. Kurt Vonnegut, with his sharp wit, noticed this irony when he said:

"For some reason, the most vocal Christians among us never mention the Beatitudes. But, often with tears in their eyes, they demand that the Ten Commandments be posted in public buildings. And of course, that's Moses, not Jesus."

This is the tragic piece of “The Missing Peace” (for more on the development of my thinking on this topic read: “What is Peace?”). We have become like the barren fig tree that Jesus cursed because it bore no fruit. Our faith—our theology—may appear healthy on the surface, but if it doesn’t produce justice and mercy, it is dead. Worse still, it often seems to produce injustice.

Take Gaza, for example. We don’t truly see Palestinians. They don’t count as much as the victims on the other side of the barrier on October 7th. And the days leading up to October 7th—October 6th, 5th, 4th—or the days that followed, October 8th, 9th, and 10th, are rarely factored into our narratives. We selectively grieve, selectively care, and selectively act.

Selective Grief, Selective Peace

Bruce’s sermon and these conversations have reminded me that Advent is a time to take stock of these painful realities. Rachel’s tears—whether they are shed for Palestinian mothers, Indigenous communities, or any who suffer under oppression—remind us of our complicity and our need for repentance.

Mitri Raheb’s insights challenge us to examine not only what we’ve missed but also what we’ve allowed to shape our theology. Too often, we’ve embraced frameworks that perpetuate harm while neglecting Jesus’ radical, restorative call to peacemaking. This isn’t just about what we believe; it’s about what we’ve failed to do.

Advent: A Call to Lament and Action

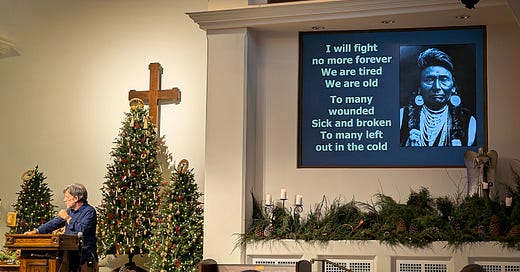

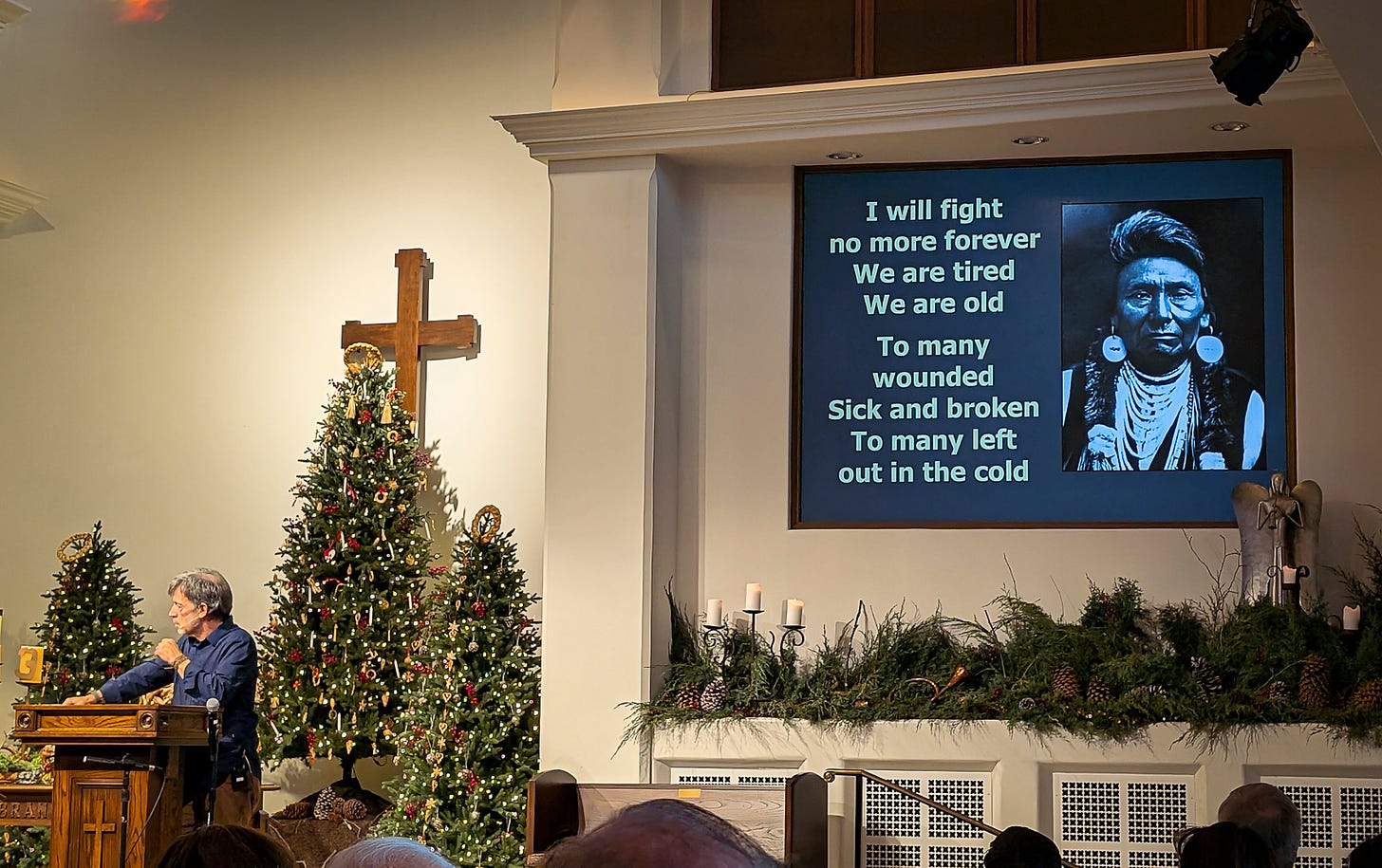

Terry and Darlene Wildman’s song “Chief Joseph's Lament” captures this so powerfully:

"I will fight no more forever, we are tired. We are old.

Too many wounded, sick, and broken. Too many left out in the cold.

Creator, send your rain to wash the earth,

to wash the blood from our hands that we would be one people."

This Advent, as we wait for the Prince of Peace, I invite you to wrestle with these questions:

Have we reduced the Gospel to what’s “just about us”?

What justice is missing in our theology?

How have we, knowingly or unknowingly, supported systems that harm rather than heal?

And how can we move from lament into action that reflects the wholeness and justice of shalom?

Advent reminds us that lament is not the end but a beginning. It’s an invitation to hold space for grief, to tell the truth about injustice, and to act for the restoration of all people.

As we light the candle of peace this week, may we not settle for a peace that is partial or one-sided. Instead, may we embody the full peace of Jesus—a peace that restores, heals, and makes all things new.